A Guide on Hip Flexor Injuries

Hip flexor and groin injuries commonly occur in many different sports and can be difficult to diagnose. Hip flexor injuries occur mostly in soccer, hockey, and track, but can occur in other sports too – like gymnastics, cheer, and dance. Some of the studies reviewed combined groin injuries with hip flexor injuries and there are few studies on hip flexor injuries at the high school level.

Most of the research on hip flexor strains involves college and professional athletes and does not differentiate between the various muscles around the hip. It can be a challenge for athletic trainers to determine exactly which muscles are involved in or excluded from hip and groin injuries. Making it even more challenging is some groin injuries may seem to present as hip flexor injuries.

For clarity, the scope of this article will focus on the rectus femoris, iliacus, psoas major, sartorius, and tensor facia latae – as these are the muscles usually involved with true hip flexor injuries. The hip has great mobility in all three planes of motion – sagittal, frontal, and transverse. In addition, a greater range of motion in the hip is necessary for sports participation (5). Discussion on this topic will include proper diagnosis, prevention of injury, rehabilitation of the injury, and return to play criteria. Identifying each hip flexor muscle, its insertion, origin, and its movements can start us on understanding how injuries occur and how they are diagnosed and treated.

The Rectus Femoris

The rectus femoris is one of the quadriceps muscles that attaches at the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) superiorly and the patella and patellar ligament inferiorly. It is the only quad muscle to cross the hip joint and flex the hip (5). Given its anterior and superior insertion, this muscle is commonly included in hip flexor injuries and Serner showed proximal rectus femoris tendinous injury occurred the most in the athletes included in his study of athletes 18-35 years old (6). Most of the injuries occurring to this muscle are from kicking and sprinting and this is also what I have observed at the high school level in ice hockey, track, and boys’ and girls’ soccer.

The Iliacus and Psoas Major

These two muscles are sometimes referred to as the iliopsoas group and originate on the transverse processes of T-12 and L1 – L5 and inserts on the lesser trochanter of the femur. This muscle group flexes the thigh and trunk (5). According to the Serner study again, 12 injuries occurred to the iliacus during change of direction and were to the musculotendinous junction, and the psoas major had a lower number of injuries than the iliacus. Keep in mind, this is just one study as a reference point.

The Sartorius

The sartorius originates on the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and inserts on the proximal medial aspect of the tibia just below the thigh and leg (5). There were only four injuries to the sartorius recorded from the above-mentioned study. So, the sartorius was one of the least injured muscles in this particular study.

The Tensor Facia Latae (TFL)

The TFL originates on the anterior iliac crest and ASIS and inserts on the IT band of the facia latae. It contracts the facia latae and assists in flexion of the thigh (5). Only one TFL injury was recorded from the Serner study. Keep in mind their study involved only 33 college athletes. I have evaluated only a few TFL injuries in high school ice hockey and soccer. Of all the hip flexor muscles, the sartorius and TFL appear to have the lowest injury rates (2,6).

Pelvic Alignment

One consideration seldom referred to in hip flexor injuries is the alignment of the pelvis. It is the opinion of this author that if it is anteriorly or posteriorly tilted or if the pelvis is rotated on one side or the other it could possibly be a precursor to a hip flexor injury because of the asymmetrical forces on the muscles involved that attach to the ASIS. Each side of the pelvis can be rotated in the sagittal or transverse plane. There is also pelvic obliquity where the iliac crests are not level and if one leg is shorter than the other, as measured from the ASIS to the medial malleolus – in my opinion- this could also contribute to a hip flexor injury (3). Pelvic misalignments are rarely discovered before an injury occurs. It is usually not part of a preparticipation examination.

Initial Diagnosis and Treatment

First and foremost, the injury must be properly diagnosed by the appropriate healthcare professional. An accurate diagnosis is critical. Be certain to understand that anterior hip pain can also be due to other conditions such as hip impingement and labral tears – which can be a much more serious injury and needs to be ruled out first.

Once an injury occurs and a diagnosis is made, rest is usually the first step and the length of time is determined by the diagnosing healthcare professional. Support for the injury can be given with a hip spica using an ACE wrap or -better yet- a 3” or 4” rodeo strap really works well. Crutches are an option too if the injury is debilitating enough and the athlete cannot bear weight. NSAIDS or other OTC medications could also be used to reduce inflammation and pain, but individuals should always check with their MD before taking any medications.

A side note for using ice on injuries:

Icing minor injuries are no longer the panacea it was once thought to be. If the athlete feels he or she must ice the area; 5-10 minutes is sufficient to reduce pain. Some current research shows icing an injury can actually delay healing. (4) That discussion is beyond the scope of this article.

Prevention of Hip Flexor Injuries

The most obvious approach to preventing any injury is adequate preparation by dynamically warming up and going through additional static stretches – if desired. It has been my experience some athletes wish to do additional static stretching of the quad and hip flexor. Warming up can be jogging a lap around a field or skating a few laps around the ice rink at a low intensity. A dynamic warm-up consists of specific movements (see table 1).

Foam rolling the various muscle groups surrounding the hip can be beneficial before and after practice/games (1). Myself and our Head Athletic Development coach – KC Bonnin also believe foam rolling helps to elongate tissues, increase blood flow to the area, and acts as a myofascial release.

Specific stretches should include a hip flexor stretch being sure to keep the lumbar spine neutral and not extending it. Michael Boyle in his book New Functional Strength Training for Sports recommends a box hip flexor stretch with the front foot elevated 6” with the body turned to a 45-degree angle to the box to increase hip flexion and stabilize the spine. The rear foot-elevated split squat is a strong movement that Boyle states “improves the dynamic flexibility of the hip flexor muscles” (1). KC Bonnin utilizes Frankenstein with grass pickers for full hip flexion and extension which he states stabilizes the opposing hip and spiderman walks and lunges are also used in his dynamic warm-up. “We use lateral lunges and banded crab walks for frontal plane stabilization” which he believes reduces non-contact injuries of the lower extremities.

Dr. Aaron Horschig, DPT, and a competitive weightlifter points out in his book Rebuilding Milo, some different diagnoses of hip flexor injuries such as: snapping hip syndrome and iliopsoas syndrome and he also reiterates most of the injuries are the result of overuse (4). This brings up the question: How much is enough training, practice, games, and conditioning? It is a challenging and difficult question to answer – especially at the high school level where athletes are in various stages of growth and development from 14-18 years of age. It has been my experience that the younger athletes 14-16 may benefit from shorter practice times and fewer conditioning drills and let subjective discomfort in the hip flexor area be a warning to stop or reduce activity for that day. This action is debatable by coaches.

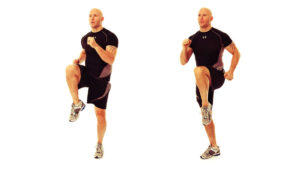

The Dynamic Warm-up:

- High knee walk

- Heel-to-butt w/ forward lean

- Backward lunge

- High knee skip

- Straight-leg walk/skip

- Backward run

Mechanisms of Injury (MOI)

From the few studies reviewed and personal experience at the high school level, kicking and sprinting was the mechanism of injury (MOI) for the rectus femoris injuries whereas the change of direction appeared responsible for the iliopsoas group injuries (2,6). Ice hockey and men’s and women’s soccer showed the highest rates of recurrence for the hip flexor strains with most of the injuries occurring in the competition which makes sense because of the increased intensity (2). In contrast to that, at the high school level, most of the hip flexor injuries I have evaluated occurred in practice.

Furthermore, it was also found that most of the hip flexor injuries were non-contact with overuse being a close second and this appears to be the same trend at the high school level. Therefore, these sports should focus on the prevention of the injury and have very specific rehab protocols and return to play (RTP) requirements since they have high rates of recurrence.

Adequate preparation and gradual progression into full-speed drills/play are key for decreasing hip flexor injuries. Forceful acceleration, cutting, kicking, change of direction, and even deceleration are the causes for most hip flexor injuries and this is why most are considered “non-contact”.

Working at the high school level the past several years, I see 8-12 hip flexor injuries every year. There also have been a few avulsion fractures of the ASIS. As a point of interest with this type of injury, I know of one 15-year-old hockey player who had an avulsion fracture of the lesser trochanter. The injury occurred in the first shift after accelerating with a change of direction. I mention this because the athlete’s MD informed me that this is a very rare injury.

Rehab

Many different modalities and treatments can be used for hip flexor injuries. Some of the more common ones include heat, ice (see side note), ice massage, hot or cold whirlpool, ultrasound, iontophoresis, PNF stretching, therapeutic exercises, electrical stimulation, massage, cupping, IASTM and positional release therapy, and dry needling. The Athletic Trainer or Physical Therapist will use the modalities they believe are most effective to reduce swelling and pain and to gradually increase the athlete’s full pain-free range of motion. Strength training exercises will begin once those goals are accomplished.

Return to Play Criteria (RTP)

Once the rehab protocol is completed, then return to play (RTP) requirements can be initiated. As stated above, the athlete should have a full pain-free active range of motion (AROM) in hip flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation. There should be no point tenderness on the anterior hip or any of the hip muscles involved with the injury. The athlete should be able to run, cut, kick, skate, change direction, accelerate and decelerate at full speed without pain.

If any pain occurs with gradual progression to full-speed movements, the athlete should remain at that level of exertion or below until the specific movement becomes pain-free – no matter how long it takes. This is the critical point where some athletes may try to push through the pain and risk reinjury to the tissues. Be conservative with your progressions! Remember that recurrence of this type of injury is common.

The challenge with rehabbing competitive athletes is their desire to return to their sport as soon as possible. They are usually very motivated and want to return to the field or ice sooner than they should. The athletic trainer or physical therapist should understand this and take the necessary precautions to return the athlete too soon and risking reinjury. Remember, hip flexor injuries can be difficult to diagnose and rehab, so be conservative and patient through the entire rehab process.

A final medical release is usually given at the completion of the rehab program. Full recovery is necessary for safely returning the athlete to any sport. I recommend an athletic trainer or strength & conditioning coach take an athlete through full speed “sport-specific” drills and participate in a certain number of practices before playing in a game to assure proper conditioning has been regained and the athlete is not experiencing any pain.

Conclusion

Hip flexor injuries occur in sports – the highest rates are in soccer, ice hockey, and track. They occur somewhat in gymnastics, cheer, and dance. The specific muscles involved are the rectus femoris, iliopsoas, sartorius, and tensor facia latae (TFL). According to some of the researchers and practitioners, the rectus femoris and iliopsoas are injured more than the sartorius and TFL.

Initial proper diagnosis of the injury is necessary to determine the proper rehab protocol. In diagnosing hip flexor injuries, labral tears and hip impingement should be ruled out – given the similarities in the presentation of symptoms. Kicking, sprinting, acceleration, change of direction, and overuse are common mechanisms of injury for the hip flexors with most injuries occurring in competition and being non-contact injuries.

» ALSO SEE: Building an Effective Soccer Strength & Conditioning Program

As with all injuries, prevention is the key. A proper dynamic warm-up prepares the tissues for greater forces. Foam rolling the hip muscles is beneficial before and after practice and games and specific stretches further prepare the body for full speed activity. The specific strength training exercises build the various hip muscles to help develop strength and prevent injury.

The final part of the rehab protocol is to follow the specific return to play (RTP) requirements for their given sport and obtain a final medical release from their MD to return to their sport with no restrictions. Obviously, there is a need for more research on hip flexor injuries – especially with high school athletes. Finally, follow these guidelines and suggestions and there is a good chance your athletes may not have to experience the hip flexor blues.